It has been derangedly hot in Space City these last weeks. Not Vegas or Middle East heat, but record breaking for our time of year. Which comes as no surprise and is a look at future summers.

This is just one of a few reasons I love H. H. Hollis’s 1967 science fiction short story “Travelers Guide To Mega Houston” (Galaxy Magazine, Vol. 25 No.06 – August 1967). Short story shorter – future Houston is now covered in a collection of geodesic domes that cured the city of all its ills. Including the city’s “anti-human climate”.

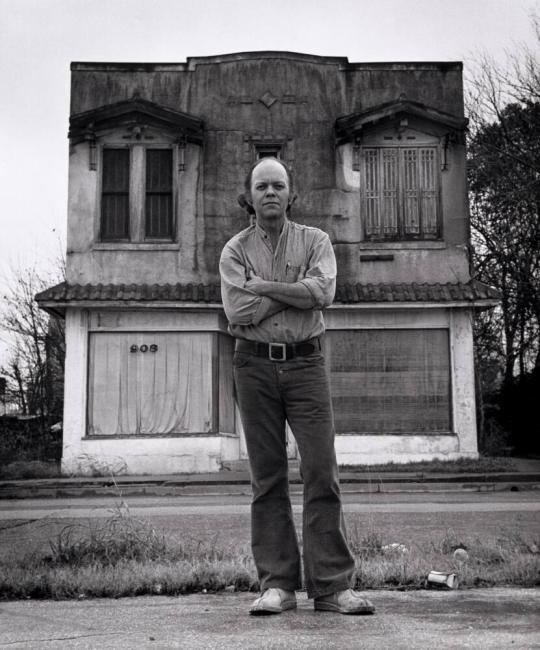

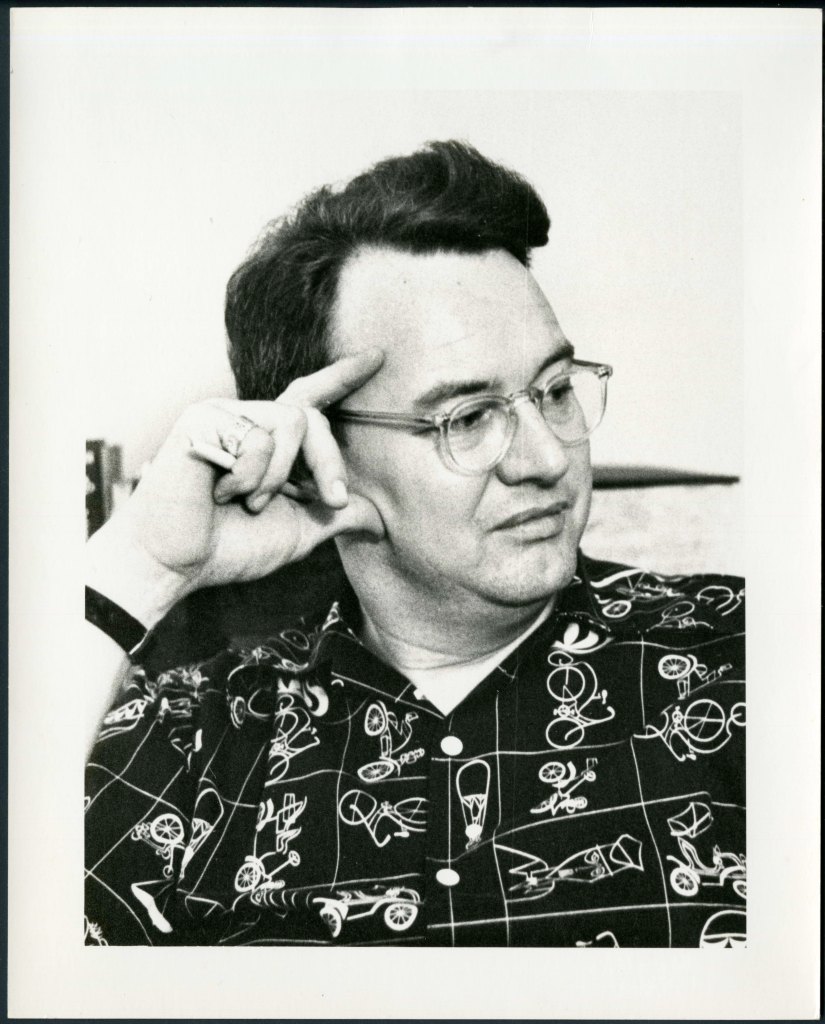

H. H. Hollis was the pseudonym of Houston lawyer Ben Ramey (October 1921 – May 1977). Not limited to the production of sci-fi writings, he was also a civil rights lawyer and member of the Houston Folklore and Music Society.

The Fondren Library at Rice University has an interesting entry on Ramey, as result of the donation of documents by the daughter of Howard Porper, a founding member of the Houston Folklore and Music Society and friend of Ramey.

Ramey’s deep involvement with Houston community and legal institutions,, which started in the 1940s-1950s, may explain his detailed explanations of how this fictional Houston transformed itself into the wonder of domed technology and all it’s benefits.

Travelers Guide to MegaHouston

by H. H. HOLLIS

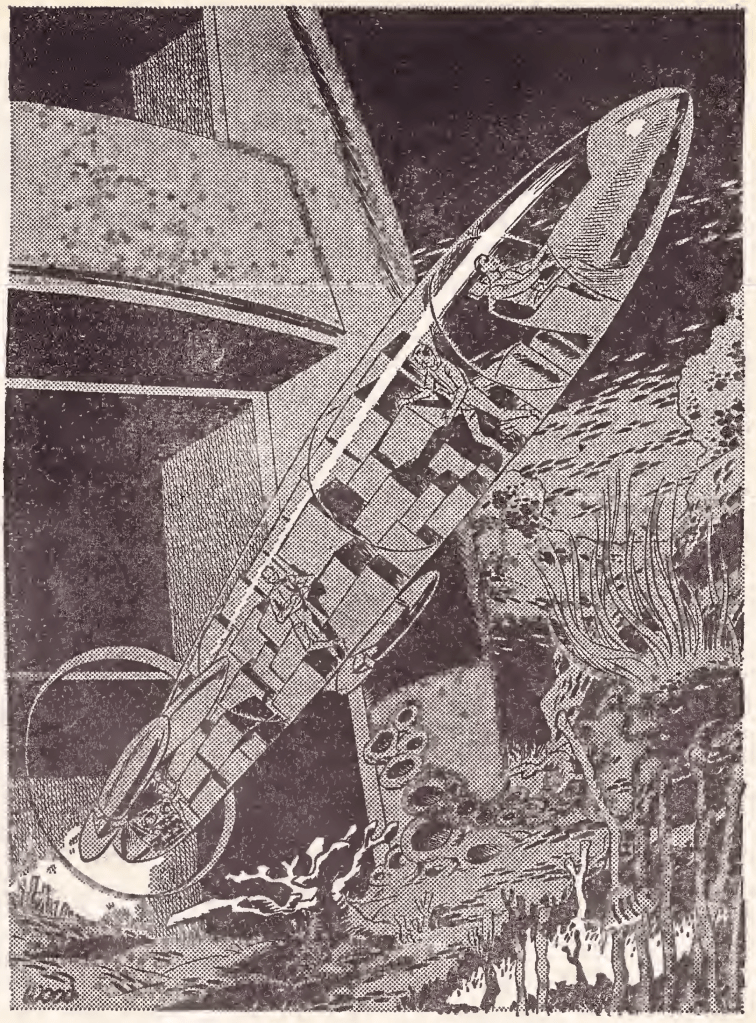

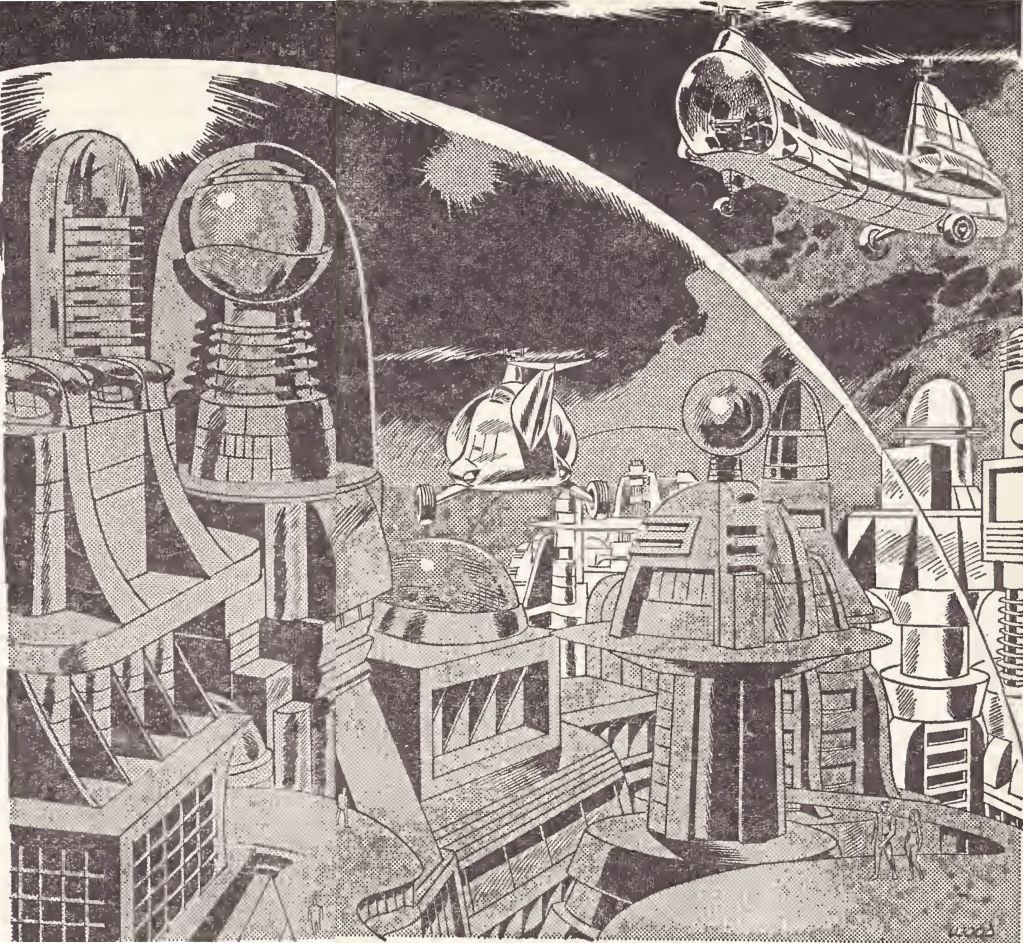

Illustrated by WOOD

When one sees MegaHouston from two or three hundred miles in space, the piled iridescent domes resemble a drift of soap bubbles spread in a sixty by-forty-mile ellipse. It is easy then to understand why an enthusiastic Houston realtor once tried to nickname his city “Xanadu.” The leathery East Texans, who constitute a significant, if diminishing, fraction of the great city’s population, disdain exotica; they call the bubbly city, with wry affection, “Cromagnoli’s Folly.”

The affection is genuine, and so is the sour taste; for these oldsters would never consciously have voted for a program to make Houston what it has become, which is something rather different from a stately pleasure dome. Chairman Cromagnoli never admits that the result was planned. He calls MegaHouston a splendid unintentional bullseye. As time passes, however, and perspective sharpens on the (apparently) aimless process by which Old Houston transformed itself into the world’s most spectacular exemplar of the age of technology, it becomes harder to accept Chairman Cromagnoli’s words and easier to believe the twinkle in his eye.

It is certain that the city founded by the Allen brothers while Texas was an independent republic did not betray much potential. for expansion until the Houston-Harris County Ship Channel was dug in 1919. Houston, as a city of any significance, was always a creation of technology; but never, until the impact of Como Cromagnoli, a conscious one. The Turning Basin, that considerable man-made lake at the foot of Navigation Boulevard which makes Houston a seaport fifty miles from the open sea, was the placid engine which generated whole families of Harris County fortunes; but there was no intellectual feedback from the Basin to Main Street. Today Harris County is beautiful and busy beneath its climate canopy because the era of technology has found its institutional expression in MegaHouston.

Other great American cities seem to have had reasons of trade or of climate to explain their being where they are. Not so Old Houston, which began as a real-estate promotion. By mid twentieth century it still stood mostly in the former flood plain of Buffalo Bayou, a short, turgid river emptying into Galveston Bay. Although the land area had been reclaimed, miasmic fogs overlay it night and morning, and the haphazard burgeoning of industry, spread through residential areas by the fact that Houston was the largest city in the world without a zoning ordinance, had begun to turn natural lowland mist into chemically fortified smog.

Buffalo Bayou had become one of the world’s most polluted waterways. The air of Harris County, already thick with humidity, was made dense with waste from Channelside industry. Automobile proliferation enriched the mix enough for the photochemical effect to take place, and a thousand poisons became visible in the atmosphere.

Engineers who might have supplied answers to the question of how to make the area livable were still being set piecemeal problems of making individual plants more profitable. Houston bragged (begging the question of its sub-tropical climate) that it was the most air-conditioned city in the world. In truth, it was not an air-conditioned city at all. It was only a random collection of air-conditioned homes, cars, offices and churches. One of the Gemini series of earth-orbiting experiments produced a profound shock to the collective Houston ego with a photo of the city made from space in 1966: a blob of haze from which rose a half dozen unmistakable columns of industrial smoke.

Yet the corner in the sweaty history: of Old Houston had already been turned in the early sixties; as usual, without anyone’s recognizing that a new era had begun. Onetime County Judge Roy Hofheinz is enshrined in Harris County mythology for having taken rain, heat, bugs and sharpshooting night birds completely out of the national pastime by, air-conditioning the ball park.”

The technical device for accomplishing the Judge’s assault on tradition already lay at hand in the form of Fuller’s geodesic dome. Stable, cheap and beautiful, this structure had been adapted for use as homes, stores, factories and churches. In the botanical gardens of St. Louis and Mexico City it even contained small rain forests and other specialized ecologies. Once a politician of stature called for a commercially feasible treatment of Houston’s climate, architects and engineers were able to draw plans based upon years of safe and satisfactory dome performance. The Harris County Domed Stadium is the cornerstone of the canopied metropolis.

It remained for a political tyro to recognize and consolidate the real significance of what the stadium began. Apparently Como Cromagnoli (already familiar with the Astrodome) was awakened to the endless versatility of the form by a visit to Canada’s Expo ’67, where the United States Pavilion was a twenty story, nine-million-dollar, acrylic and steel geodesic bubble. But the central elements that combined in him to reshape the lives of so many millions are two: he was once a Houston school teacher exposed to the political storms which periodically wrecked the Houston Independent School District, and he was later a clerical employee of the Houston Harris County Ship Channel Navigation District, the (seemingly) non-political body which administered the Houston Ship Channel and its appurtenances.

The audacious but oblique first step toward putting Houston under glass was the political campaign in which Cromagnoli unveiled himself to public sight. With money supplied mostly by a well known engineering and construction firm, the former schoolteacher ran for the school board. In doing so, he disdained not only the traditional content of Harris County politics, but also the traditional objectives. The school board, though powerful and wealthy, had always been a graveyard of ambition, far from the historic levers of power, where the best of good wills were somehow manifested only in ugly, archaic political brawls. When elected, he held the one swing vote in a seven-member board, which elected Cromagnoli chairman because there was no other way to get the board functioning. He first restored the meetings to television, where they had once been the most popular show (a kind of excruciating situation comedy) on the University of Houston’s educational channel.

In a totally unexpected move, Cromagnoli then asked, on camera, if any member of the board had any program sufficiently worked out to be on paper. This was a real violation of board etiquette. Traditionally, members had depended entirely on staff for any writing more demanding than epithets or yeas and nays.

Gavelling down the “hems” and “haws” of board members, who were caught as unprepared as first graders at a spelling bee on the second day of school, Cromagnoli reached into his portfolio for a thick handful of papers. Over the years, that gesture of the chairman, fraught with threat and promise, was to become a cliche of the televised board meetings.

As he held up a large sheet and beckoned the camera to him in a tight closeup, Como Cromagnoli had in his hand the bomb which was to shatter Houston’s complacency, culture and economy. It was a beautiful architectural rendering of O’Brien and Rockwell’s comprehensive design for a twenty-acre educational park with interrelated buildings for elementary, secondary and junior college level scholars, all contained in a glittering jewel of a dome. Old Houston fell in love with that picture, with all its startling implications.

The building of the school dome posed many problems, and the solutions often seemed to require the creation of some new industry in Houston. The Texas Gulf Coast had long been a center of the heavy chemical industry, and the exacting specifications of the Houston Independent School District and its architects for the plastic components of the dome were at last met only by the creation of a new plant capable of extruding the high impact, clear, scratch-resistant sections with the close tolerances that would keep the structure leakproof against Harris County’s hundred and fifty per cent humidity.

Money was never a problem; for members of the social work community, who had become as skilled at grantsmanship as the James Boys had been at horsemanship, fell to in teams to write multiple applications that would exact the last dollar from HEW, OEO, NIH, Urban Affairs, Transportation and the Texas State Department of Education in Austin. To accomplish the job, they suddenly found themselves cheek by jowl with people who spoke mathematics as their first language. The idea that both groups had real functions in society was as startling to each as the discovery of a new sense organ would have been; and the big bubble cross-wired pools of skill whose whole previous existence had been independent of each other.

Although Houston had, in years past, used thousands of tons of air conditioning, most of the machinery had been fabricated elsewhere; but the enormous dome raised design problems no one in the industry had ever contemplated before. In the end, a team of engineers and philosophers detached themselves from the faculty of Rice University, got their radical ideas underwritten by one of the two Houston banks claiming to be the largest in the South and, after a precariously functioning demonstration, successfully bid in the air-conditioning contract.

The work was made difficult not only by the immensity of compressors and heat exchangers, but also by the design requirements that ducts should not mar the dome and that the air, once cooled, had to be kept on the move through twenty acres of park and buildings. The conventional response, erection of | ventilating towers containing ducts and air returns, was turned down by the board as too factory-like. Air-conditioned trees (with ducts and blowers concealed in their leafy branches, like . those already in use at Six Flags, Texas’s answer to Disneyland) were rejected on the ground that machines small enough to be concealed in trees could not move enough air for the whole hemispherical space which was to be conditioned.

The suggestion to air-condition the buildings separately imperiled the whole project for a short time. It made little sense to dome the institution, if the buildings were to be supplied with individual machinery. A cost study was run up which showed a saving of millions by choosing this compromise; but after some soul searching, the board again voted for the project as originally dreamed.

RiceProCo, Inc. (the Rice Professors) solved the problem, both in terms of technique and of money, by making the air enclosed in the dome do most of the work. The space was large enough, after all, for the outside heat to cause convection current inside. By modifying a little laboratory tornado maker into a reliable sort of air churn, great masses of air could be made to move themselves without creating fierce drafts. The resultant saving over the use of blowers and the increased efficiency from realizing much of the potential energy in the air mass enabled the job to be done with a quarter of the horsepower called for by the conventional solutions.

As the patrons of the school district stepped into the balmy air of the school dome on “Open Dome Day,” and the sweat began to evaporate while they looked up through the clear beauty of glass and lucite, so that they knew it worked, thousands of individual resolves were born.

Within a week, O’Brien and Rockwell were inundated with demands for dome designs, large, small, residential, commercial and manufacturing. Every architect’s office in Old Houston plunged into the competition, and City Hall was besieged with applications for dome building permits. Proposals ranged from the absolute functional beauty of the basic design through such refinements as solar glass to the ultimate faddishness of baroque domes encrusted with seraphim and magnolia blossoms of cast concrete. One famous Houston recluse ordered an opaque bubble of stainless steel. The design for a celebrated collector of modern art had each module an eyestraining work of optical art done in stained glass.

Structures such as those now proposed had no place in the city’s building codes, yet there seemed no way in which to restrain the proliferation of the hummocks. What had been approved as a container for a ball park and an educational center could hardly be denied to textile manufacturers who saw the elusive goal of real humidity control within their grasp or to private citizens of means who suddenly understood that real control of their personal environment was now available for purchase.

About a hundred bubbles were built before their geometrically increasing numbers made it apparent that social control of some sort (abhorrent though the concept was to most Houstonians in any other context) would have to be exerted or the whole machinery of the city would be disrupted beyond repair.

The loveliest of these wild domes is that erected by Burton Claridge, the sprightly spinster heiress who always referred to herself as Houston’s maiden aunt. Her domed home was the old lady’s last building effort, and it is a magnificent hybrid which has drawn on Hagia Sophia in Istanbul for its architectural shape. That is, the building is a dome resting on a square base. The square prism of mellow pink Mexican brick surrounds what was an entire city block, and is unrelieved by any opening, save the great black iron front doors and the more utilitarian truck and delivery entrance on the back street. The “house” is the square, with the rooms surrounding the open center of the block. More than a dozen live oaks and five lofty pines were saved in this great inner court and can be seen from outside, thrusting up their crowns in evergreen promise. Air gates for squirrels and birds are in each quarter of the dome, just above the supporting brick walls, so the trees are alive with song and movement. The dome itself has each of its hexagonal modules, framed in aluminum anodized in the color of gold, so that the trees appear to be enclosed in a cap of gilded lace.

As might have been expected of its builder, this superb edifice and the ground on which it stands were willed to the people of Houston by Miss Claridge, and the home in the brick square now houses an art collection, a historical library and. an unsurpassed library of recorded music. It is one of the city’s most beautiful and most used parks; but few of the other wild domes were built with such an eye to public utility.

Now that MegaHoustonians are all used to the arching domes that enclose the city and its neighborhoods in an orderly fortress against Harris. County’s anti-human climate and affect, when showing a visitor about, a blase acceptance of the canopies, the campaign to assure the adoption of the master-dome plan has been all but forgotten. But it was in that campaign that the unified pride of MegaHouston was forged.

As a consequence of Old Houston’s lack of a zoning ordinance, the most exclusive of residential neighborhoods had been breached again and again by lumber yards; sheet-metal factories and the ubiquitous blighting convenience of the shopping center, which brought the grocer, the barber and the intimate little restaurant within walking distance, and rats, roaches, all-night neon signs and full load traffic as well. Even the city government sometimes seemed to be enlisted in the war against livable neighborhoods, as sewage and garbage disposal plants appeared overnight in residential areas. Citizens were resigned to he swift destruction of property values and green space.

The circumstances which combined to bring about the harmonious, comprehensive and logical plan, now seen to be so effective, must include the moving to Houston in the 1950’s of the major oil companies’ chief executive offices.

Old Houston had ceased to be a mere regional capital. Its establishment came to include a majority of men who commanded broad social responsibilities as well as great wealth. Next came the NASA administrators, wielding kingly powers on bureaucrats’ salaries and charged as a duty to utilize technical resources to the utmost for purposes on which political agreement had been reached.

The other end of the financial spectrum included the sprawling masses of Houston’s poor in the antique wards, creeping along the Bayou to the waterfront, and their reluctant allies on the North Shore, the high hourly wage workers whose high wages had never kept them from being vulnerable to the business cycle. They shared a conviction that private development of the domes would leave them in the humidity and pollution of industrial Houston, once more (and perhaps forever) on the outside looking in. Zoning had not moved these groups to vote. Doming did.

A famous engineer joined the dean of the new school of social work and a noted anthropologist in a statement which summed up the ideological content of the campaign. It began:

“Technology, by cutting the Ship Channel, created Houston as we know it, in a place where no large concentration of human beings ought to be. In the proven technical device of the dome, we have the instrument with which to ward off the less desirable features of our climate. In the Houston Harris County Ship Channel Navigation District, we have a managerial system capable of extending this engineering blessing fairly to us all. Eet us entrust the power to remake Houston as we want it to a governing body with a history of honest and intelligent administration of the technical substructure on which Houston already depends and from which Harris County has already grown rich. We have wealth. Let us get health.”

Houston’s right-wing weekly newspaper, which went out of business a few months later with a proud record of never having supported a winning candidate, attacked the master dome plan as a device for Sovietizing Hosen right-wing weekly newspaper,

Harris County. This publication also unwittingly gave Cromagnoli the priceless opportunity to give a name to his formless movement. A questionnaire was sent to him which included a query as to his political identification. “I am,” he wrote, “a Technical Democrat.”

By voting in local option elections in large and small communities and in the county at large, the people of MegaHouston can now be seen to have adopted a new way of dealing with the problems of giant cities. They have never, in any subsequent election, failed to vote for what they have come to call “humane technology.” Every step of its development has flowed from the technical requirements of the multiple domes.

The billion dollar bonded indebtedness which burdens the citizens of the District (and pays such fantastic dividends) was dictated by the engineering calculations. The walling off of the Ship Channel industrial area into its own “Crystal Palace,” that immense tentacle of glass and stainless steel, was a compromise between the old what’s-a-littlesmell-in-the-air lobby and the engineering recognition that to let channelside pollution back into the other domes was to defeat their purpose. It was costly to build the overhead tunnel “which winds along one shoulder of the crystal palace (“this airborne sewer,” one commentator called it), but providing that . common conduit for the discharge of industrial wastes made it possible for Channelside industry to oppose the canopy. And today, the heat-borne waste elements are reclaimed by standard precipitation techniques in quantities sufficient to pay for the pension of the District’s employees.

Once the poisoned air of industry was contained, control of the polluted water of the Ship Channel followed as just another technical problem. Certain Netherlands and Norwegian shipping companies which formerly refused cargo for or from Houston because the water of the Channel was so corrosive to hulls are now happy to bid on MegaHouston shipping.

Since diesel and steam exhausts and the dumping of spent bunkers to form inflammable oil slicks are now all forbidden, vessels are brought up the Channel entirely by power supplied by the District at a price which is negligible compared to the expense of collisions in the old days. The power to move the ships was first supplied by electric tugs; but now comes from “magnetic mules” which grip the great ocean-going vessels in an invisible web and silently glide them up and down river, observing the rules of the road by electronic communication to each other. The electric tugs were built in Houston, since they existed nowhere else, and are now exported to many ports which have begun to attack their own pollution problems. The magnetic mules are another product of the ingenuity of an academic research group, in this case one from the University of Houston (UHuRanD Corp.), and their manufacture is one of a host of new industries summoned into being by the genie of the canopy.

The mere question of ingress and egress spawned the profitable light industry of canopy openings, those simple.yet efficient machines sensitive to body heat, which expand to allow a person or a small animal to pass through and quietly close behind him. (They were originally called sphincters, but the biological analogy was a little too graphic for some imaginations.)

The water gates on the Channel represent another manufacture of Houston origin, useful wherever the volume of air to be controlled is too large for any device which actually opens and closes to accomplish the objective; and where the job to be done is of sufficient economic importance to warrant the expenditure of significant sums of money. The device, popularly known as “the electronic whirlpool,” is a simple molecular sorter which creates a statistical anomaly of positively charged molecules of the major gases composing our atmosphere. The anomaly has its physical existence in an invisible wall (a local violation of the principle of entropy) about four feet thick. The warm, slightly contaminated air beyond the end of the semicylindrical glass shed does not push through this impalable barrier, and on the near side of it the silent, gliding, deep-sea vessels are within the conditioned air of Houston.

The electronic whirlpool is very expensive in terms of the power required to operate the machine, for refusing to accept entropy in a gas not contained in a closed volume is a neverending process which does not even remotely approach stasis. Designing and manufacturing such entrances has become an enterprise as profitable as constructing monumental statues for public buildings once was. Since many airports, even in cities not themselves air-conditioned, are now domed (or roofed, as the municipal airport is at Wichita, Kansas), insubstantial entrances are in great demand. Various adaptations may also be seen at the several fields surrounding New Washington, and with particular success at San Francisco, where fog is no longer a problem because of the domed airport, and at Chicago, where even the shrieking winter lake winds are tamed by the electronic vortices.

The four aerodromes at the points of the compass around Houston demonstrate the different airport designs. At the private plane port to the west of MegaHouston, the dome is simply pierced by sixteen circular openings, in each of which a molecular sorter operates to keep cool, dry air in and hot, rainy air out.

The big cargo field has “trapdoor” openings sufficiently wide and high to accommodate even the most immense of the knockdown cargo crates. The traps snap open at radar signals and when the cargo planes are twenty miles (one minute) out and already locked into their glide path. During the interval of slightly more than a minute that the upper and lower halves of the trap are opened into the dome, a simple forced-air curtain maintains the separation of inside and outside air.

This is only tolerable for cargo. Passengers require greater comfort and elegance than these glorified garage doors can give. The secondary advantage of the dome for cargo is that its height easily accepts — indeed, dwarfs —the cranes and gantries which disassemble the bodies of the flying crates into their constituent containers; and the virtual absence of weather inside makes it possible to store the containers in orderly annular dumps near the ring wall, so that a cargo plane can be stripped of its outer shell, reduced to the erector set skeleton, serviced, re-containerized, re-shelled and flown back out of Houston’s Air Cargo Port in fifteen minutes. It is the boast of MegaHouston’s freight solicitors, who are active in every cargo capital of the world, that delays in turn-around for a cargo plane occur only from waiting for the trucks to bring freight in, and never from handling.

The short-haul jet field dome has been equipped with openings that resemble giant camera shutters. They are triggered in the same way as the “garage doors” at the cargo port; but for the greater comfort of those inside the dome, a molecular sorter is in constant action behind each shutter, and there is no interchange of inside and outside air except for that which is inevitably dragged in during the instant when the little two-hundred-passenger needle noses disrupt the curtain.

At the long-haul jet dome, which must service the thousandpassenger global carriers which in appearance so resemble the boomerang, it has been found necessary to create a sort of storm door of air. The sorters are here modified to project a cylinder from the great openings through which the transports must land. The outer end of the transparent cylinder is disrupted by the passage of the enormous goose wings, but it is instantly re-established. The tubular walls bulge, but contain the outside air; and little enters the dome when the plane tears through the inner face.

Houston Hot Air Doors, Inc., one of the manufacturing arms of RiceProCo., Inc., stands ready to bid on the design and installation of these “doors” anywhere in the world; and the success of the company is evidenced by the fact that it trades in forty currencies.

Apologists for the new era are quick to point out that the most important thing about the doming of Houston has not been the comfort imparted by the process, but its generation of new industries, products and jobs. Aside from the fact that the original process, with its fits and starts and errors, soaked up unemployment of even the least skilled workers in the area for half a generation, the present form of the domed city has spawned innumerable new approaches to problems which once seemed insoluble or incapable even of being attacked. Pneumatic public transport illustrates those specifically cityrelated industries which MegaHouston has developed. Connoisseurs of rapid intra-city transit claim that the network of vacuum tubes buried under MegaHouston is the fastest and most luxurious form of mass transport ever achieved and is of unparalleled safety, because both “cars” and “tubes” are of plastic sufficiently yielding to give with the shifting of Houston’s soft subsoil, and the compressed air which fills most of the system at any one time serves to keep the whole thing blown up against soil pressure as if it were a serpentine balloon. Perhaps the distinguishing feature of the system is the flexibility which has allowed it to replace the auto for most purposes. (Even the so-called “exhaustless automobiles” are not used in the domes.) The pneumatic tubes branch to every single city block in MegaHouston. The constantly moving capsules are fully private, if desired. Parties wishing to travel together link elbows as they step onto the loaders, the auxiliary loops which accelerate one from standing still to a velocity matching that of the capsules. Once a capsule has expanded to accept a person or a group, it is impervious to any other passenger or to any hooligan or criminal until its load has been discharged.

And the school dome is now the only one which employs the first model of the modified tornado-making machines. In the rest of MegaHouston, the gentler, improved air-churns operate to move the masses of conditioned air so easily that the real motion is imperceptible. Children derive so much pleasure from the more palpable eddies in the school dome that they have been allowed to remain. The towering spirals also serve to introduce children early to their command of large technical forces and to the necessity of dealing with them in a technical and knowing fashion.

On exceedingly hot days, the spirals elongate to deal with the greater load imposed on them, and it is then possible to confide to the care of the smaller ones sheets of paper, light personal belongings and even textbooks on some days. Making them visible with colored calsomine powder has fallen out of favor. Since they are double spirals, the objects tossed to them are carried up the center and then back down the outside helix as if by an invisible servant. The four largest ones will sometimes in midsummer, when they labor hardest, carry a child, if he is small; and there is great competition among the first graders to be lifted on the shoulders of the high schoolers and junior-college athletes to the point where the tornado touches down. To do this requires the making of a pyramid of at least three tiers, since the point of the spiral is never closer than fifteen feet to the ground; and the child who trusts himself to the whirlwind must also trust himself to his older comrades to hand him up the human slopes and at least give him to the air (and of course, to retrieve him at the return point of the outer helix). Valuable lessons in cooperation are learned without the children’s ever becoming aware that anything is being taught. The newer machines are more efficient, but they will never have the charm of the first set.

The domed city is characterized also by extruded houses. Where the air does not corrode nor destructive wind destroy, fancy may be given full reign in a living shell; and the machines that deposit the shells will follow any model that is placed in the sensing chamber, much as a key-making machine copies the tumbler ridges of the original key. MegaHoustonians live in eggs, silos, n-sided polyhedrons, and in replicas of Monticello, Mount Vernon and Belle Reve. In and out of these pleasant homes, MegaHoustonians wear locally manufactured throw-away clothing. Where most dust is filtered from the air, paper shoes are as handsome as they are cheap.

There can be no doubt, however, that of the new industries germinating under the canopy like plants in a terrarium, the most revolutionary and the one which has had the most nearly world wide economic impact is the manufacture of soft plastic tankers for the petrochemical industry. The principle of the submarine tanker had taken drawing-board reality by the middle sixties. Once it was recognized that putting the whole ship underwater did away with all that superstructure of the traditional ship which required so much maintenance and the addition of the nuclear, propulsion plant eliminated most of the space formerly occupied by diesel or electric motors, it was a short step to rationalize the whole operation by reducing the rigid structure of a tanker to a single module which required a crew of only four men. “Houston Tankers” are long cigars of clear plastic. Direct vision eliminates the need for gauging; and each section within the tubing has a valve on the side that is taken by a line coupling resembling the mechanical milkers which industrialized dairy farming in the middle of the twentieth century. The tanker is sailed into the specially constructed pens, and hydraulic pressure milks each section of its cargo. Loading is accomplished by first squeezing a section flat with the pressure of sea water, then pumping the water away from the side and letting the resultant low vacuum inside the section pull the cargo in from the tank farm. Ports not yet equipped with the special pens can use their shoreside pumping equipment. Each tanker carries short lines with a milker at one end and a conventional metal collar with a flange at the other for coupling to old fashioned pumping lines.

Need it be said that all this, which now seems to have been almost inevitable, in fact happened with many faltering missteps pae the master plan, it was thought that not all parts of the canopy needed to be domes.

Under this impression, some extremely wasteful and impractical structures were created. One of these resembled a great circus tent of clear, flexible plastic supported by aluminum girders anodized in bright primary colors. It enclosed a thirty-acre tract which was developed for quarter-acre house lots. The selling gimmick which doubled the lot prices was pressurized with an extra pound of straight oxygen, so that a slight euphoria was induced. The euphoria vanished, along with the promoter and the flimsy canopy, on Labor Day of 1974, when a tropical storm that had gathered her strength for three days between Yucatan and Galveston suddenly roared north and shredded the polyethylene film with hundredmile winds. The domed structures survived almost without a leak, and the members of Old Houston’s middle class who suddenly found themselves living in unairconditioned but expensive houses were thereafter among the most vociferous supporters of the idea that canopies ought to be built and maintained by some agency of society so that risks could be equitably shared by all citizens.

Clear polyethylene film continued to recommend itself because of its low initial cost. One design, hung pyramidally from a single central mast, disappeared at the beginning of a week of rain when the mast was struck by lightning. A non-conducting metal was next used for the mast and the design modified to a cone; but something in the constant friction of the air moving within the cone charged the normally inert plastic film, and the cone called down a ball of lightning whose plasma flittered and yawed for half an hour over the apex and then lit the whole plastic sheet out of existence in the blink of a flash bulb.

The last trials of non-rigid plastics were made with simple inflated hemispheres. The pull and push of the coastal winds inexorably wore seams and fastenings to the breaking point, and the soft hemispheres were relegated to sports events and home shows. The expertise gained has proved, like so much else of the long experiment Houston has become, to be marketable. Since the inflated hemispheres are entirely practicable for short periods, the business of erecting and inflating them for athletic events has made badweather insurance a thing of the past for American promoters. A hemisphere, compressor and a crew can be hired for less than the premiums on such insurance. Even the engineering failures served a purpose. Canopy building pulled in unskilled and unemployed workers as the living sponge pulls in food-laden seawater. Frantic urgency got dome raising into operation by every known building method, so it was no surprise to see one construction rising from a ring of bulldozers and giant earth movers and its neighbor employing eighty-year-old mule _ skinners to grade earth tossed up by pick-and-shovel gangs of fifty-yearolds who hadn’t had steady work since the end of World War Two. Fortunately, Houston (and nearby Mexico) abounded with job bosses who had experienced this same amalgam of new and old as La Republica shouldered her way into the family of industrial nations. Much of this hasty work had to be redone. But before that happened, a generation of workers who had thought themselves discarded by society were given regular paychecks and selfrespect, and the endless appetite of the project for better trained personnel created a pressure on the schools which made those old strongbacks the last generation of illiterate workers in Houston’s history.

The largest factor in rebuilding was not, after all, the haste of the original construction, but the necessity for relocation and resizing of dome units to conform to the master plan laid down after the renamed Houston Harris County Ship Channel Navigation and Air Conditioning District became the only real governing body within the confines of Harris County.

When the empowering act of the Legislature of 1975 became law, the era of private canopy erection was over. The grid which underlies today’s glittering complex of domes was laid down, and the first rational city of the industrial age came into institutional being. A wise discrimination had ever since balanced the demands of humanity and of technology in an equation which slights neither.

Anyone who has ever seen MegaHouston from the air or asked directions of the relaxed, technically oriented citizens who populate the great city has understood at once the functional simplicity and grandeur of the city’s present design.

Harris County was divided first into four quadrants, with the intersection of the north-south and east-west axes placed, for sentiment’s sake, at Texas Avenue and Main Street, where the capitol of the Republic of Texas once stood. There rises the grandest of the airy bubbles in which MegaHoustonians live and work, with Chairman Cromagnoli’s transparent office at its very apex, the eagle’s aerie from which all is visible. To the cardinal points of the compass, four lines of domes extend, their bases touching. Twenty-eight other points of the compass bear diamond bands of domes to the perimeter, each culminating in a large dome. The radii to the lesser points of the compass begin several miles from Dome One, on a circle with Texas and Main as its center.

Street curbs and sidewalks in each quadrant are of a distinctive color; so that directions to a home may begin by naming the quadrant of residence by direction or by color: “I live in the southeast (blue) quarter,” and continue: “in the twenty-second dome on the south south by east point, finishing with the direction inside the residence dome: “on the west side of SSE 22, near the perimeter, block 62.” Within the residence domes, there is no uniformity of streets, so the human desire to live “somewhere different” is given full play. Some of the “villages” have cobbled streets on which George Washington would feel at home, some are paved with poured plastic as shimmering and smooth as glass, and some have no. streets, only walks. Fuelcelled ground-effect cars, floating on their cushions of air, are the only vehicular traffic allowed within the domes, and the constant vacuuming of the narrow streets and walks which goes on through the scarcely visible slots at the edges of every pavement prevents any dust from being raised by the cars. Internal combustion engines, whether they burn fuel oil or gasoline, are allowed only in the freight domes next to the airports and at the returning basin on the Channel.

The circular base of every dome in Harris County touches at least three other such bases. The consequence is that there are spaces between the domes. The intersecting arcs of the bases shape four, five and six-pointed stars on land which are outside the domes; and a wise decision has been to keep these enclaves not just green, but wild. It is possible to obtain a permit to cultivate an orchard, but it is rarely given, and the produce must be left on the trees for the use of the public and the wild animals (squirrel, possum, raccoon and armadillo, mostly) who have established themselves. The purple figs in the five point on the southwest curve of dome fourteen west southwest by west are justly famed; and there are several pecan groves made glad each fall by the disputations of small boys and squirrels over the nut crop. Perhaps the most delightful of the groves is that through which wanders one of the short, sluggish bayous. In the spring, it is made beautiful by the blossoms of the hard, tart, red peaches planted in Texas first by the Alabama Coushatta Indians; and in the fall, swatches of crimson betray the red haw, the fruit of which boils down to jelly of a flavor wild and indescribable except in terms of itself.

prom Park has been domed as an entity — zoo, golf course, bridle path, planetarium, Medical Center, equestrian statue of Sam Houston and all — but Memorial Park has been left as the greatest of the unroofed enclaves. There those who are nostalgic for the mosquitoes and midges of Houston’s humid past may refresh their memories of the time before the canopy. Many do so. There is even an eccentric preacher who roams the park prophesying that MegaHouston will disappear in thunderbolts because it is the new Sodom, and calling on the “Xanadites” to repent while there is still time. He has about as much following as Lot had in Sodom.

The “Reeepent Man,” as he is called, would not have been tolerated while the skeleton of the canopy was being fleshed out with plastic and air-conditioning, but MegaHouston is so incontrovertibly a wonder now that it can afford criticism from any quarter. The Houston Harris County Ship Channel Navigation and Air Conditioning District has been given the taxing and financing powers of an independent state. Chairman Cromagnoli, with twinkling ruthlessness, has moved from the school board to the District. He still calls himself a “Technical Democrat,” as do most of his fellow citizens, even those who vote Republican in state and national elections. The requirements of technology have so transcended Houston’s past as a southern city, committed to the “peculiar institutions” of the Cotton Kingdom, that there is no longer any significant emotional content to old bigotries. MegaHoustonians have grown used to attacking problems on a technical level and so conscious that informally learned prejudice (whether against large bonded indebtedness, physical comfort or neighbors of a different culture) dissolves when problems are formulated in technical rather than in ethical terms, that even the oldsters approaching senility, who might have been expected still to have emotional responses as automatic as snapopen doors at a supermarket, can be heard declaring about Some new idea, in their slow drawls, “Ye-a-ess, I feel like it’s wrong; but let’s talk about how we could do it, if we wanted to; and then let’s cut back and see how we feel about it.”

t is easy to look back now and see that the impulses to control the environment fully, which had its start in the modest, inexpensive Astrodome, created such technological demands that there was simply no profit in maintaining the old fictions. The raising of the canopy in its multiple domes became the overpowering concern in the life of every Houstonian, as in an earlier age the raising of Mont St. Michel and Notre Dame had been the overpowering concern in the lives of medieval Franks.

Houston’s inhabitants had been sensitized to technology for three generations, from the day the first dredges began to cut out the Turning Basin between Navigation Boulevard and Six Bit Street. In three generations, the petroleum and chemical industries proliferated and upgraded their products. In their own lifetimes, many Old Houstonians saw natural gas grow from being a nuisance that was burned freely in the air to a profitable

industrial fuel, and finally to a raw material of the plastics industry and even to a chemical component of food, in laboratory experiment. When this informal history was expanded by the importation of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, and technology was yo-yoing into space people you could run into on the street, the ground was fertile and the Harris County Domed Stadium was a viable seed.

The solution of Harris County’s twentieth-century problems — urban sprawl, diluted government, dissipated tax base, air and water pollution, encysted poverty, black-white-and-bronze power — all lay at hand, in technical programs of varying complexity; but to call these programs into being required some central project that could seize men’s minds and hearts as revolutions and revivals do. As the Xanadites of MegaHouston look up through the clean, clear bubblés that have made their city famous, they can be conscious that in Cromagnoli’s Folly they have invented more than a few machines and a new way of doing something about the weather.

They have invented the politics of technology.

—H. H. Hollis